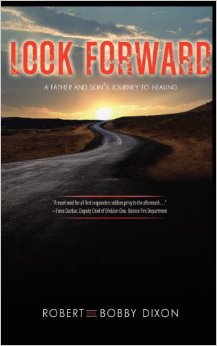

Look Forward

Chapter I: China

If I close my eyes I can go back to that first night in Bobby’s room in the trauma ICU. He is in a deep coma and his body in its outward appearance does not betray any signs of the severe damage that has been done to his brain, spinal cord and internal organs. He is near death, pale and motionless, but he is alive.

For now, Bobby is like a newborn baby. He is completely reliant on others for his survival, but unlike a newborn, the people that will save his life, or at the very least, forestall his exit from this world, are a collection of strangers. They are a menagerie of doctors, nurses, medical technicians and others through whose expertise he has so far stubbornly clung to life. As I watch his slow breathing aided by a respirator and see the web of tubes emanating from his body, I know it is only a tenuous hold.

Sitting alone watching him there is a hum to the ICU that will become as much a part of my life as had been the daily ebb and flow of Shanghai’s ever busy streets and continuously moving people. I will learn the schedules of his doctors, become used to the movements of the nurses through his room as they feed and bath and care for his motionless, struggling body, and come to know many of the technicians who come to his room. As they go through their various ministrations, his face, like that of a sleeping baby, will make some expression of sensation. I am never sure why, but I know it is a good thing.

Seeing him there, in his bed being taken care of by so many I am reminded of what it was like to watch him when he was a baby. Before work each morning I would check in on him in his crib and give him a gentle pat to say goodbye, and then at the end of the day I would look in on him again, first thing, without fail.

During the night, if I got up, which was a relatively common occurrence, I would look in on him in his crib to be sure he was all right. Over the intervening years, though, I had forgotten how good it felt to visit with him while he slept and how proud I was to be his father, to be this little boy’s dad.

It has been 32 years, but the feelings and emotions are the same. I feel good that I am with him in the ICU, I’m thankful to have a son like Bobby, and I am incredibly proud of him. His life is one that is unique to him as each of our kids’ lives is unique to their personality, likes, dislikes and interests. These idiosyncrasies are reflected in the choices he has made in his life, which like cairns along a mountain path are markers leading to this moment.

Of course, I did not always agree with his choices. That first night in the ICU after having traveled for more than 30 hours from China, I could not talk to him about those choices or the directions our lives had taken. I could not share with him my profound sadness at having been so far from him, nor could I apologize for what I may have done or said during many conversations between us that quite frankly did not go so well.

Watching him in an apparent state of sleep I knew that I love him, I knew that I was proud of him and I prayed to God that he be allowed to live; that we have the chance to continue our lives and perhaps improve our relationship. This is not to say that I believed I was a bad parent, but when confronted with the imminent death of a son or daughter, it is inevitable that one’s mind would reflect on last conversations and disagreements of the past.

Like any father/son relationship, ours had its ups and downs. There were many things that we found to disagree on and for a period of time we lost contact with each other. However, in the couple of years preceding his accident, we had rebuilt our relationship and I was very proud of Bobby and how he had overcome a host of obstacles to build a life that I think was pretty good for him.

Even still, there were stresses on our relationship. Mine was a life that was spent traveling for work mostly in Asia. Despite the distance we remained close, but I didn’t see him much. I was always gone and the distance between the Northeast United States and Shanghai, China, was enough to make speaking on the phone a challenge.

Life was busy as most people’s lives are, but with the time difference, all the issues we had to deal with around coming home for two week stretches at a time—needing to go here and there, do this and do that—made life chaotic. It was to the point where many times when I was home I didn’t get to actually see him, though we might talk on the phone.

Most of our relationship was carried on through text messages. In fact, Bobby would text message me a lot while I was in China. I might get 15 or 20 text messages from him in the course of a day, during meetings, middle of the night, they simply arrived all of the time, and most of them were just silly things. We only really had substantive conversations or picked at our disagreements when we spoke over the phone.

Thinking of these things as I watched his chest heave uncomfortably, forced to inhale and breathe by the respirator, all of our disagreements seemed so insignificant. Often I felt he wasn’t listening or taking my advice on some important matter. I thought he focused on issues and items and things that didn’t really matter, that wouldn’t move his life forward. Invariably, if we fell down this path our phone calls wouldn’t end the best way you would want them to. My own frustration would probably come out around that and weigh on Bobby; and me as well.

Sitting in the ICU I knew I had to let these thoughts go; that the time to address these issues with Bobby would be later, if there is a later. However, I could not help but wonder how the last phone conversation went, and feel some sense of regret that we couldn’t have worked through our differences before now. If I could have been prepared for this, if I could have known what was coming I would have probably done some things differently. However, we don’t get to choose the time, the place or the moment in which our lives are turned inside out and thrown into chaos. There is no time to prepare. It just happens. We wake up as we do every other day expecting the sun to rise, the earth to turn and life to continue much as we have experienced it throughout our lives. Our relationships and lives simply continue and evolve and we assume they will always exist as they are because they always have.

In the midst of all this ordinariness we see the tragedies of others around us; the family that is lost to fire, bombings in other countries, fatal car crashes that make the news, and we think how sad for them. Then we turn the page, click to another website or change the channel and don’t give another thought to what these horrible events mean to those individuals, their families and the people that inhabit their world. Many of us are simply obtuse, but for others we arrogantly believe that these things don’t happen to our people. We are immune to the vagaries of life and fate.

The day of Bobby’s accident started as every day before it had. It was morning in Shanghai and I had gotten up and started my routine. Because driving in China can be both complicated and hazardous at the same time I had a car and driver that would pick me up in the morning and take me into the office. The driver had arrived that morning, but there was a nearly impenetrable fog. Shanghai is a coastal city on the East China Sea and thick fogs are relatively common there. I think the visibility that day was around 150 feet and given the recklessness with the way many of the Chinese sometimes drive, the municipal officials simply shut the major highways down when visibility is low.

My driver and I sat around my apartment and I started to do some work in preparation for arriving at the office to what was very likely going to be a fairly busy day. I was already late due to the fog and it was my first day back to work in China after having had the previous two weeks off. My driver was calling around to some other drivers he knew to see where they were and how bad the fog was in an effort to try and figure out what time we might be able to leave.

I had talked to my wife Kristy earlier in the morning not long after waking up and everything was fine. The phone for Kristy and I has always been a lifeline between us. Ours was the life of two people who both had stressful jobs and from the time we had met. Kristy is Bobby’s Step-Mother and we have worked in different cities, either across the U.S. or the world, for most of our time together. To bridge the physical distance between us we speak to each other multiple times during the day and without fail, every night at 9 pm east coast time we would talk.

I’ve actually left meetings with the presidents of very large Japanese, Chinese, American or other corporations in order to be able to call home at 9 pm. It is one of those rules that we have never broken and to this day have not stopped. I am lucky to have her in my life and without any doubt, she is my best friend.

Soon the fog in Shanghai began to clear and my driver nudged me to say let’s go. As we were getting ready to leave I called Kristy just to say hey we are going and that I would call her later, before she goes to bed. However, when she picked up the house phone it was obvious she was talking with someone else on her cell phone. I could hear her side of the conversation and I got a sense from what she was saying that there was a problem.

She kept telling me to hold on, wait a minute as she tried to figure out what the other person was saying. It seemed like someone had been hurt, but I didn’t think at first it was anyone I knew. Soon Kristy said okay and asked that person to call her back when they knew more. Then she came on the phone with me and said Bobby has been in an accident.

From what she said and I suppose the way she said it, whatever happened it didn’t seem to be that bad. I just assumed that Bobby had been in his truck and had some sort of minor accident.

“No,” she said, “He was on a motorcycle.”

I had no idea he owned a motorcycle and I wondered why he had not told me he bought one.

Still, I thought to myself that Bobby probably had some bruises and scrapes, maybe a broken bone, but Kristy didn’t think from talking to Bobby’s girlfriend that he was hurt too badly. I asked Kristy to find out what she could and to let me know whatever she finds out. I closed my phone and my driver and I headed to the car and started off to the office.

Kristy and I had an arrangement whenever she wanted to call me. First she would send a text message to my U.S. phone and I would call her back on my Chinese cell phone because it was much less expensive. The trip to the office takes about 30 minutes, but we hadn’t gone more than a mile when I received a text message from Kristy. Usually her messages would say, “Call me when you get a chance,” or something like that, but this time the message only said, “Call.”

I called her and the first words she said to me were, “It’s bad.”

China was the culmination of more than 30 years of hard work. In 1977, I’d left the Air Force after eight years, which had been a very difficult choice for me. I had no college degree and hadn’t been able to take anything close to a college course except for the last year or so of the service, but those few classes didn’t really add up to much. I didn’t know what my future even looked like or what was possibly out in the world, in civilian life for me without a college degree or very many prospects. But Bobby and his brother had come into the world and my wife, his mother, wanted me home. I wanted to be home with them more so for that reason alone it was the right choice, but it was a difficult decision.

I had no idea where or how I would find a job that would pay enough to take care of my family as well as provide the opportunity to learn and advance myself into a meaningful career. Just before my discharge I went for a disability physical in Boston.

At about the same time, I learned that Honeywell was having an open house near the VA hospital for prospective employees. I didn’t really know what they made or did, but they were looking to hire so I cobbled together a resume and stopped in.

After waiting around for a while I managed to get an interview with an HR person, but I wasn’t really qualified. As she was telling me that there really wasn’t anything she could do, the regular thanks-but-no-thanks speech, a guy who had been walking by heard her mention I had been in the service. He stopped for a moment and asked her if he could talk to me. She said sure.

He came into the room and asked, “What kind of work do you want?”

I didn’t really know what to say so I asked him if he had a job in mind that he wanted to fill.

“Does it matter?” he asked.

“Probably not,” I said. Then I asked him how much it paid and he told me $250 per week. That was $100 per week more than I had been getting in the Air Force. I took the job.

That guy’s name was John Behn. He took a chance on someone he knew a total of two minutes. He gave me a career and, in many ways, the life I have now. I don’t know what would have happened if I had struggled to find a job. I don’t think I would have accomplished all that I have been able to do. After I worked for him for a while, I asked why he hired me as he did. He said he’s a veteran too and we needed to stick together. I’ve hired two people the same way he hired me and they turned into some of the best professionals I ever had working for me.

I worked for Honeywell for nearly ten years and in the course of that time I traveled to Europe, Australia and Asia working on a number of complex projects for them. This in turn led to more jobs with greater responsibilities until I was able to form my own consultancy. On the day of Bobby’s accident I was consulting for a semiconductor capital equipment supplier as well as periodically guest lecturing at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in their MBA and China Leaders in Manufacturing programs run by MIT and a handful of interested Corporations. I was making a pretty good living for myself.

I’ve always joked it’s not bad for a guy who graduated from night school at Worcester College.

However, as proud as I was of the work and what I had achieved, I was probably away from home 65 percent of the year and in one year I think I traveled almost 200,000 miles. So most of my life was spent working and living more than 7,000 miles from the home and life I shared with Kristy. I had friends in China with whom I was close and Kristy would come to Shanghai once or twice a year, but it was a life that I found alternately rewarding and lonely.

It also pulled me away from my responsibilities as a husband and father. When Kristy told me that Bobby’s crash had been bad, I felt this aspect of my life more sharply than I ever had before. It was also mixed with a shot of adrenaline and before I said anything more to her I touch Jack’s shoulder and pointed my finger pack towards the apartment and said to him, “Jack, we’re going back to the apartment.”

As we talked Kristy told me she didn’t have many details other than that he is unconscious and they are evaluating him, but it’s pretty bad. I wondered to myself, “What do I do now? Where do I get more information? How do I get more information? Who do I know who can get this information?”

I asked Kristy if he was alive and she said, yes, but beyond that nobody had any answers.

I called my brother Sam in Connecticut and told him what had happened and asked him to go to the hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts, where Bobby was. Kristy was already on her way from our home in Southern New Hampshire, but the closest relative was my brother Richard who only lived about ten minutes away. It was about 9 or 9:30 at night back home when I called and asked him to get to the hospital as fast as possible and find out any information he could. I knew that if anyone was going to get information quickly in a crisis it would be him. Then I started calling people at the company I consulted for to tell them I was going home. I had to get home.

At my apartment I packed a change of clothes and got some other stuff together; things that I thought I would need, but at that point my thinking had kind of become a blur. I was far more focused on my deep need to get home. I called United Airlines on one phone and then American Airlines on another. I spoke to representatives of both airlines at the same time and told them I had to book a flight right away. United said they had seats available on a flight that left in a couple of hours so I booked that flight, which went from Shanghai to Chicago and from there to Boston.

By now Richard had arrived at the hospital and from what he was able to gather from the police and first responders, he knew that Bobby had been hurt very badly. He didn’t tell me then, but according to the EMTs who treated Bobby at the scene, they didn’t expect him to live very long.

As I waited with my driver and the woman who took care of my apartment, both of whom I consider to be good friends, Sam and Kristy reached the hospital. I felt badly for all of them because at that moment they were Bobby’s closest living relatives. They had an enormous responsibility that I had asked them to take on. If there were going to be difficult decisions that needed to be made quickly, those three were the ones that were going to have to make them. I felt badly, but I also knew that if there are any three people who could do it, it would be them.

With each call from Kristy and Richard it seemed as if the hole that Bobby had fallen into continued to get deeper and deeper. None of the news was good and all of it pointed to the possibility, if not the likelihood that Bobby would not survive this; that he would die before I could be with him. My sense of frustration, panic and helplessness became more and more profound at both the silence of the phone and then the information that would be conveyed to me when it did ring. There was little I could do and there was little information that I held in my possession other than that my son was dying.

I felt an intense sense of guilt that I wasn’t with him; that I was 8,000 miles away. “Why am I doing this job? Why am I over here? Why do I have to be here at this point, on this day of all days?” All of these thoughts went through my head and it was all too easy to beat myself up over the choices that had led me to be so far away. “I shouldn’t be here, I should be home, I should have a normal job, and why aren’t I there?”

It was an overwhelming feeling of total helplessness because I could not contribute anything to what was happening to my son, to the situation in the hospital and all that surrounded these events as news spread to our family and friends and Bobby’s mother who lived in Florida. I simply couldn’t do anything to help him or anyone. All I could do was wait for the phone to ring and pray to God each time that it wasn’t Kristy calling me to say he had died. I knew it would be her that would deliver that horrible news. It had to be. As I thought of that, I understood again how immense the responsibility was she and my brothers had taken on for me and how painful and difficult it must be for them as well.

I wanted someone to tell me it would all be okay. I said to myself that this stuff doesn’t happen to me or my people and for a brief moment I truly wanted it to be someone else’s problem. I wanted to shift this to another or to fix it and make it all okay. I wanted to be with the people who care most for me; people I can hug, who know Bobby, who know my life, my history and my love for my son. Instead, I was 8,000 miles away and though with people I considered to be friends, I felt alone.

I was angry, too. I was angry at Bobby for buying that motorcycle and then for not telling me he had done it. I was angry that he would have chosen a motorcycle rather than his truck to deliver a movie in the evening, in November. I was angry at whoever it was that hit him and wondered if that person had been drunk or negligent, or in some other way culpable for causing my son so much pain and making me feel this way.

For a moment, at least, I wanted to run away and hide from this; shut off the phone and ignore the possibility of more bad news finding me. I wanted to believe that people were just exaggerating how bad it was, that this was more an act of human nature to distort truth rather than believe the truth of what my son was going through so very many miles away.

And I felt pain. No parent wants to see their child in this situation or any situation that is dangerous to them or even merely unhelpful to them. I knew that whatever was wrong with him, even if I could be with him, I couldn’t fix him medically. I was dependent upon people that I had never met, who I could not see and did not know to save my son’s life, and that was painful to realize. I don’t care whether your child is 25, 35 or 45, you want this to go away and it still affects you as if they were 5-years-old.

Most of all, I was angry at myself for not being there. There was guilt; a lot of guilt.

However, you don’t get to pick the time that these things happen. You don’t get to pick the place, the when, the how, or even the why because life simply doesn’t work that way. Looking back, I had to come to the realization that whether you are 8,000 miles away or a few moments away, something like this doesn’t happen because you weren’t there.

Bobby didn’t have his accident because I was in China and I needed to realize that, I needed to end my guilt trip, but it is an easy thing to fall into; to get lost in these thoughts as your mind wanders through the horror of what is happening to you and your child. But it is unhelpful because you really need to focus on the things that you can do or should do to either help influence the outcome or to simply understand what it is you need to do to move forward.

That level of clarity had not come to me yet as I waited in my apartment to leave for the airport. It would, but for the time being I was lost in a far off country, in an unfamiliar new world, with just one thought: I must get home.